Memories carved by ancient Arab Beduins on stones

Rawan Al‑Adwan

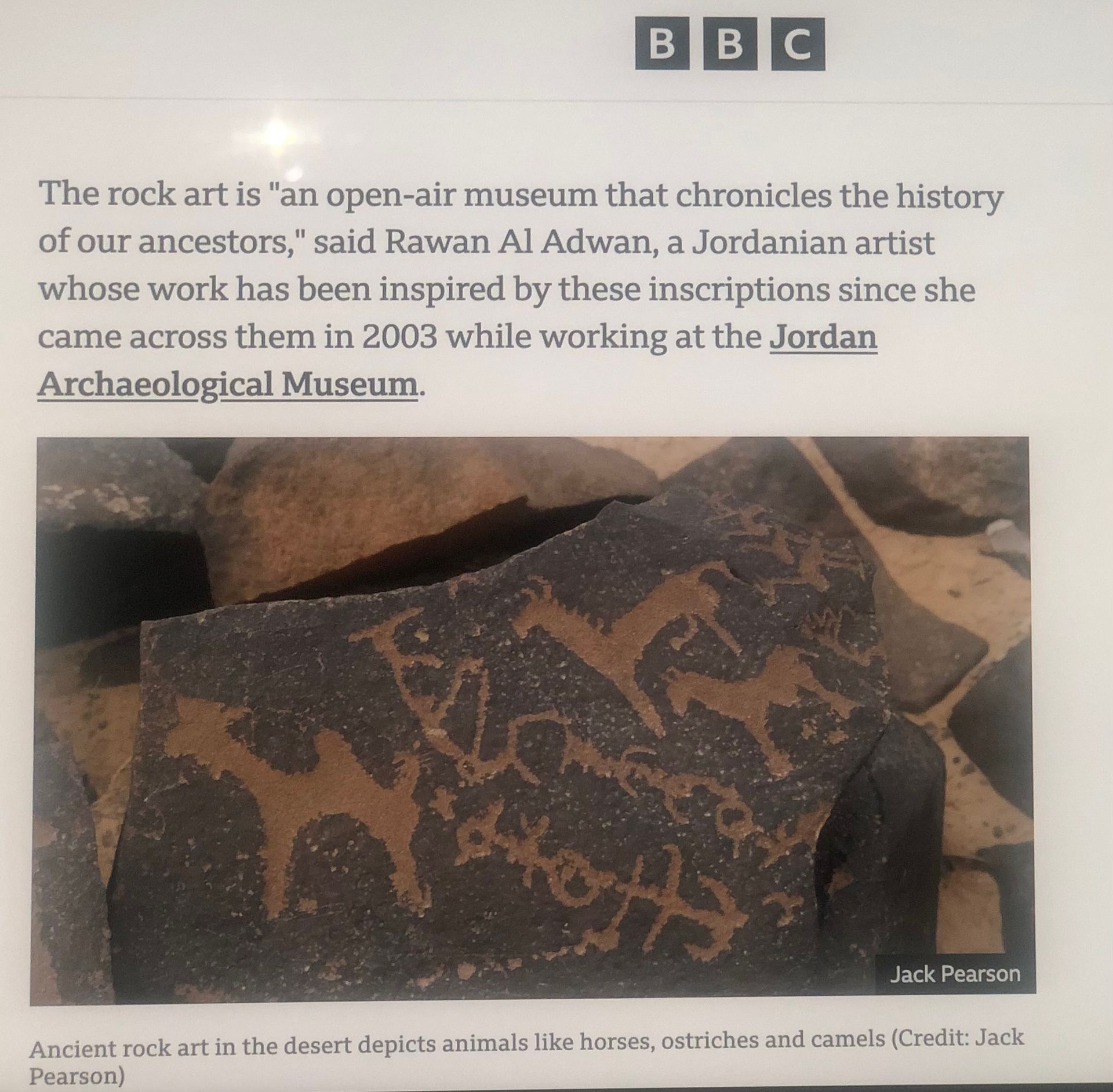

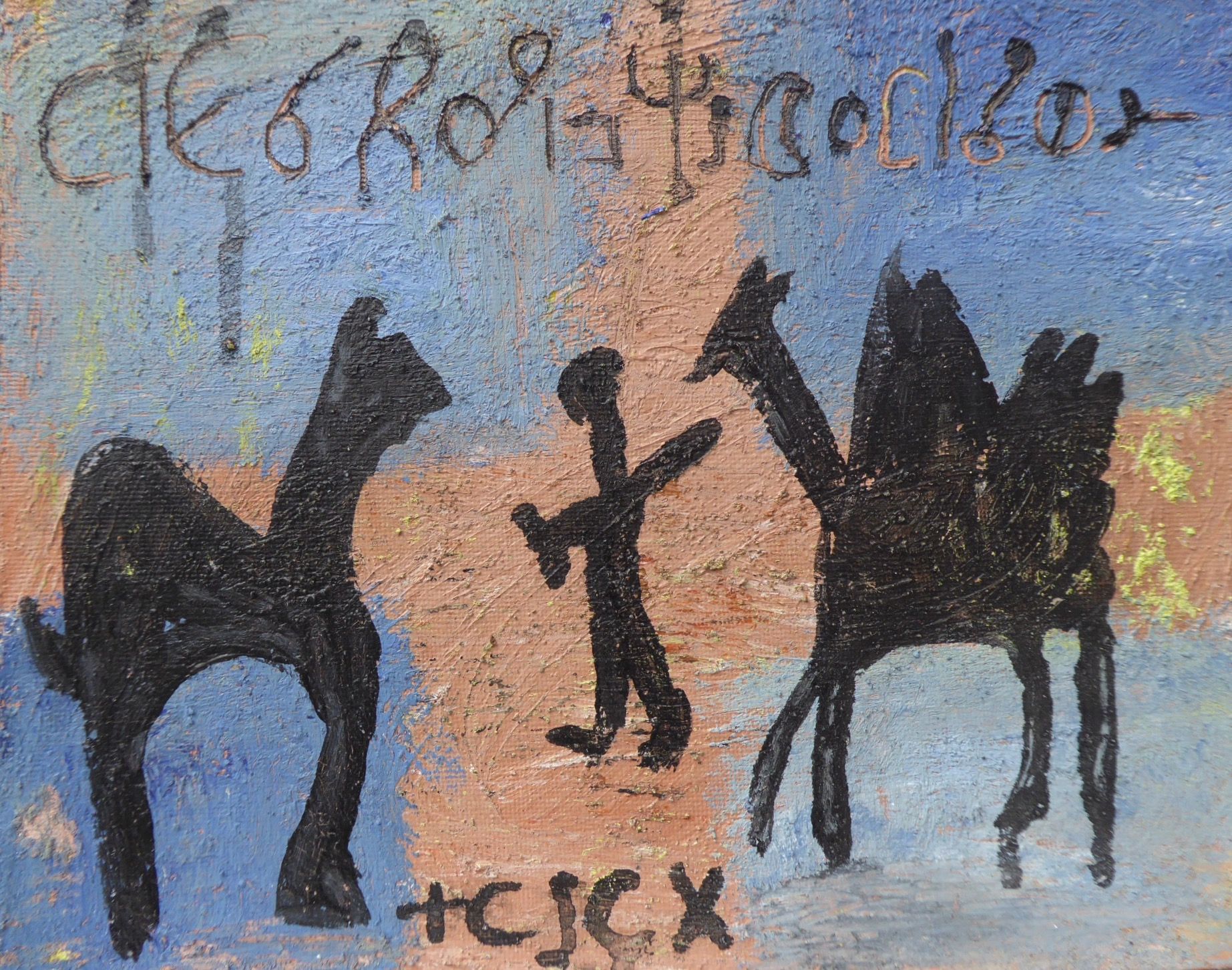

Across the basalt plains of the Jordanian Badia—stretching from the desert steppe to the distant horizon—Safaitic inscriptions and engravings appear like silent tongues that speak of a deep human history. Each carving is more than a mark on rock; it is a compact narrative of a whole life, a voice from the past whispering of worries and journeys, of joy and supplication, of rituals and celestial observations, and of social systems and tribal identities rooted in the desert.

History and symbolism

Safaitic graffiti belong to the collective memory of the Badia. Some of these inscriptions are estimated to date to more than 500 BCE, while other studies indicate their continued use across later centuries. The precise chronology matters less here than the recognition that these texts and images constitute a material archive of the lives of the Arabian Bedouin in antiquity—recording their despair and joy, their hopes and daily practices.

Every inscription tells a story

For the ancient Bedouin, an inscription was both a personal and a communal record. Names and tribal epithets identify individuals or owners: markers of camel or herd ownership, signatures that confirm someone’s presence at a particular time. Short poems thread through the letters, announcing pride, mourning loss, or invoking protection from unseen forces. At times an image—a camel, a human figure, or a sword—suffices to conjure a scene: a caravan’s journey, an intertribal meeting, or a deliberate act to secure memory. Some texts are ritual in nature, intended to guard graves or to discourage their desecration.

Worry, joy, and supplication

Many inscriptions repeat formulas of lamentation over a lost person or prized camel, and expressions of joy at a safe return or success. Brief religious or protective petitions appear as well—appeals for safety from storms, thieves, or predators. These overt acts of supplication carved in stone show that, despite the harshness of the desert, its inhabitants maintained a sustained spiritual dialogue: the worldly and the heavenly were not separate but deeply interwoven.

Rituals and movement

Numerous inscriptions point to seasonal and transitional practices: the opening of grazing seasons, caravan readiness, fears of drought, and occasional references to local cult places or collective rites. Movement is a persistent theme: crossings of vast space, recurring routes, and place‑names carved to mark stopping points or pastures. In this way the inscriptions form an early human map of pathways and networks—sometimes accidental, sometimes intentional—linking people across the landscape.

Celestial bodies and symbols

Stone panels often include references to the sky. Symbols and linear signs suggest the sun, moon, or stars; geometric motifs might represent astronomical observations or calendrical cues tied to seasons. Bedouin culture has long relied on the heavens as a guide for seasons and direction, so it is unsurprising to find that relationship etched into the rocks of the Badia.

Art and language

The Safaitic script is characterized by economy and strength: spare strokes and simplified symbols that convey large meanings. Texts are frequently accompanied by drawings of humans, camels, and weapons, giving them a visual dimension that complements the linguistic content. This blending of word and image reflects an artistic sensibility that did not treat beauty as an end apart from life but as integral to daily existence. In many ways the visual abstraction and symbolism prefigure concerns later explored by modern artists such as Picasso and Matisse.

Memory and preservation

Safaitic inscriptions are an invaluable repository of the historical memory of the Arab Badia. They bridge the lives of contemporary Bedouin communities and a long past of desert existence, offering direct evidence for the values, concerns, and necessities that shaped their identities. Protecting these inscriptions from erosion, vandalism, and encroachment—and continuing their study with rigorous, ethical methods—is a cultural obligation and a testament to our shared humanity.